New Delhi: Against the backdrop of the G20 Summit in New Delhi, India and the US have agreed to resolve their final outstanding trade dispute lodged with the World Trade Organisation (WTO), relating to restrictions India had imposed on the import of poultry from countries impacted by avian influenza (also called ‘bird flu’).

US Trade Representative Katherine Tai, who made the announcement Friday, also said that as part of the agreement between the two countries, India also agreed to reduce import tariffs on some American products such as frozen turkey, frozen duck, fresh blueberries and cranberries, frozen blueberries and cranberries, dried blueberries and cranberries, and processed blueberries and cranberries.

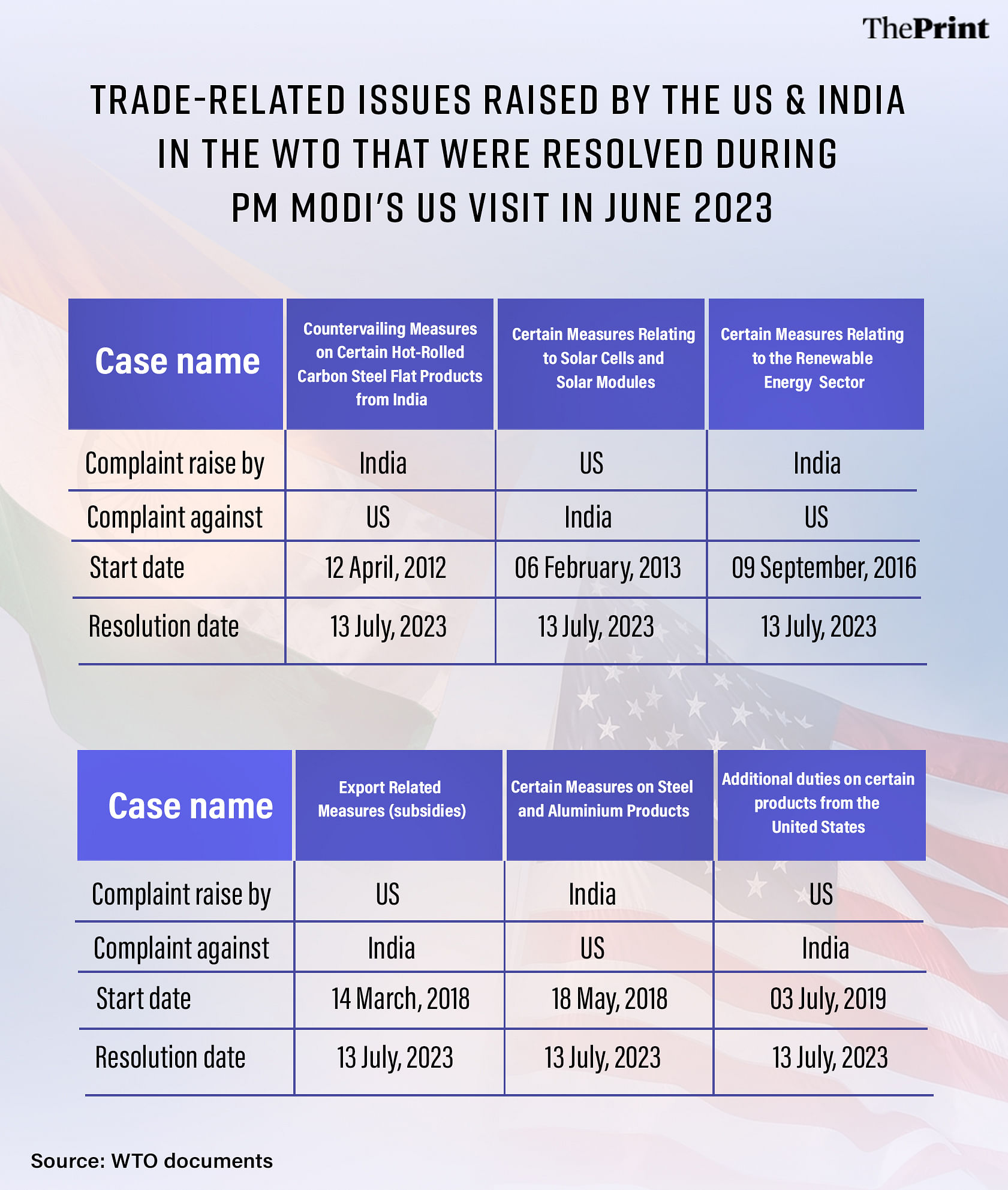

The resolution of this dispute comes on the back of the resolution of six other disputes during Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to the US in June.

The specifics of what the resolution entails have not been made public as yet by either the US or India. India’s ministry of commerce and industry has not yet released a statement regarding the resolution of the dispute with the US.

The crux of the last remaining dispute was that the US was of the view — and had approached the WTO in 2012 for arbitration on this — that India’s import restrictions on poultry ran afoul of several provisions of the WTO Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures (SPS Agreement).

These provisions had to do with the fact that such trade measures were to be taken following a risk assessment, should be based on appropriate scientific evidence, and should not be discriminatory against a particular country, among other facets.

In short, the US complained that India’s measures to ban the import of poultry from the US in order to protect itself against avian flu was not based on a risk assessment, was not backed by scientific evidence, was excessively trade restrictive, was not in conformity with international standards, was discriminatory against the US, and that India was not being transparent about them.

“Resolving this last outstanding WTO dispute represents an important milestone in the US-India trade relationship, while reducing tariffs on certain US products enhances crucial market access for American agricultural producers,” Tai said during her briefing.

She added: “These announcements, combined with Prime Minister Modi’s state visit in June and President Biden’s trip to New Delhi this week, underscores the strength of our bilateral partnership.”

ThePrint reached the ministry of commerce and industry spokesperson for comment via calls and messages, but is yet to receive a response. This report will be updated if and when a response is received.

Also Read: Key takeaway from Modi-Biden meet: India, US reiterate commitment to collaborative cancer research

How did the dispute begin?

Since around 2001, India has been taking periodic steps to restrict the import of poultry in light of the avian influenza, under the Livestock Importation Act, 1898, which was amended in 2001.

The latest of these decisions was announced in July 2011, following which the US in March 2012 requested consultations with India on the issue of “prohibitions imposed by India on the importation of various agricultural products from the United States purportedly because of concerns related to Avian Influenza”.

These consultations presumably did not go well since, in May that year, the US requested the WTO for the establishment of a dispute resolution panel to look into the matter. In June 2012, the WTO’s Dispute Settlement Board established a panel and in February 2013, the composition of the panel was also finalised.

In August 2013, the panel said it would issue its final report by June 2014. The report was finally circulated among the WTO members in October 2014.

What was the US’s issue with India’s measures?

The contention of the US was that the actions taken by India went against at least 11 articles in the SPS Agreement, not to mention several others in the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), 1994. These included but were not limited to Articles 2.2, 2.3, 3.1, 5.1, 5.2, 5.5, 5.6, 5.7, 6.1, 6.2, and 7 of the SPS Agreement, and Articles I and IX of the GATT.

Articles 2.2 and 2.3 and 3.1 of the SPS Agreement deal with the provisions that WTO member countries should ensure that any steps they take to maintain sanitary and phytosanitary standards are applied only to the extent necessary to protect human, animal or plant life or health, is based on scientific principles, and is not maintained without “sufficient scientific evidence”.

The articles also say that member countries should ensure such actions “do not arbitrarily or unjustifiably discriminate between members where identical or similar conditions prevail” and that the measures are based on international standards.

The provisions in Article 5 dealt with the assessment of risk and the level of measures that needed to be taken to ensure sanitary and phytosanitary conditions. These basically reiterated that the points that measures taken should be based on an assessment of risk to humans, animals, or plants, should be based on scientific evidence, and should not be excessively trade-restrictive.

Articles 6 and 7 of the SPS Agreement said that countries should recognise the regional spread of contamination in the country of origin. That is, trade measures should take into account the fact that contagion might be limited to only parts of a country and not all of it. They added that countries should be transparent about their decisions.

What was India’s argument?

India’s main argument was that its avian influenza measures “conform to” an international standard — the Terrestrial Code laid out by the Office International des Epizooties (OIE), now called the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH). In particular, India argued that its actions were compliant with the provisions in Chapter 10.4 of the Terrestrial Code, which dealt with ‘infection with high pathogenicity avian influenza viruses’.

If this was so, India argued, then it could be presumed that it was also in compliance with other provisions of the SPS Agreement, including those requiring a scientific foundation, and the GATT 1994.

Further, India argued that it was not under any obligation to provide to the panel the scientific risk assessment it had conducted and that its measures were based on scientific principles and evidence in accordance with Article 2.2 of the SPS Agreement.

WTO panel’s findings & India’s appeal

In its report, the WTO dispute resolution panel found that India’s avian influenza measures were inconsistent with Articles 3.1 and 3.2 of the SPS Agreement because they were not based on Chapter 10.4 of the OIE Terrestrial Code, contrary to what India had argued.

In addition, the panel said India’s measures also did not conform to Articles 5.1, 5.2 and 2.2 of the SPS Agreement because they had not been based on a scientific risk assessment, and found them in contravention of Article 2.3 because they “arbitrarily and unjustifiably” discriminated between members and were applied in a way that constituted a disguised restriction on international trade.

Then, the panel also found that India’s measures were more trade-restrictive than necessary — placing them in contravention of Articles 5.6 and 2.2 of the SPS Agreement. It also said that the measures were inconsistent with Articles 6.2 and 6.1 of the SPS Agreement because they did not recognise disease-free areas and areas of low disease prevalence.

Finally, the panel found that India had flouted the transparency requirements because it had failed to comply with a number of notification and publication requirements.

In short, the WTO’s arbitration panel found that India’s trade measures were not based on international standards, were not based on a scientific risk assessment, were arbitrary, unjustified, and discriminatory, and were done without making the adequate provisions to warn other member countries.

India appealed the decision in January 2015, challenging several of the panel’s findings. However, the appellate body of the WTO ruled in June 2015 that the panel had been correct in its decisions.

In July 2015, India said it intended to implement the changes that the WTO Dispute Settlement Body had recommended based on the findings of the panel, but that it would need a “reasonable period of time” to do so. In December that year, the US and India agreed that the deadline for implementation would be 19 June, 2016.

Past deadlines, arbitration

Following the passing of the deadline, the US requested the WTO DSB to suspend concessions to India because India had failed to implement its recommendations. India objected to the level of suspension of concessions and said that it had in July and September 2016 not only complied with the recommendations, but had also amended them to further satisfy the US. It thus called for arbitration over the matter.

The arbitrator said it would circulate its decision by March 2018. However, as recently as February 2023, it said that it had accepted joint requests from the parties to postpone the issuance of its decision, which it expected to issue in May 2023.

That deadline, too, passed. The matter now stands resolved as India and the US have reached an agreement.

(Edited by Gitanjali Das)

Also Read: Joint space crews to protecting Earth from asteroids — Modi & Biden shore up science partnership