New Delhi: India has made significant strides in reducing multidimensional poverty, but the pace of this progress has been uneven. This is starkly evident in national capital Delhi, where multidimensional poverty has decreased in some districts, but increased in others.

The latest NITI Aayog Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) report, released in July, revealed a decline in the share of people living under multidimensional poverty in Delhi, from 4.43 per cent in 2016 to 3.43 per cent in 2021.

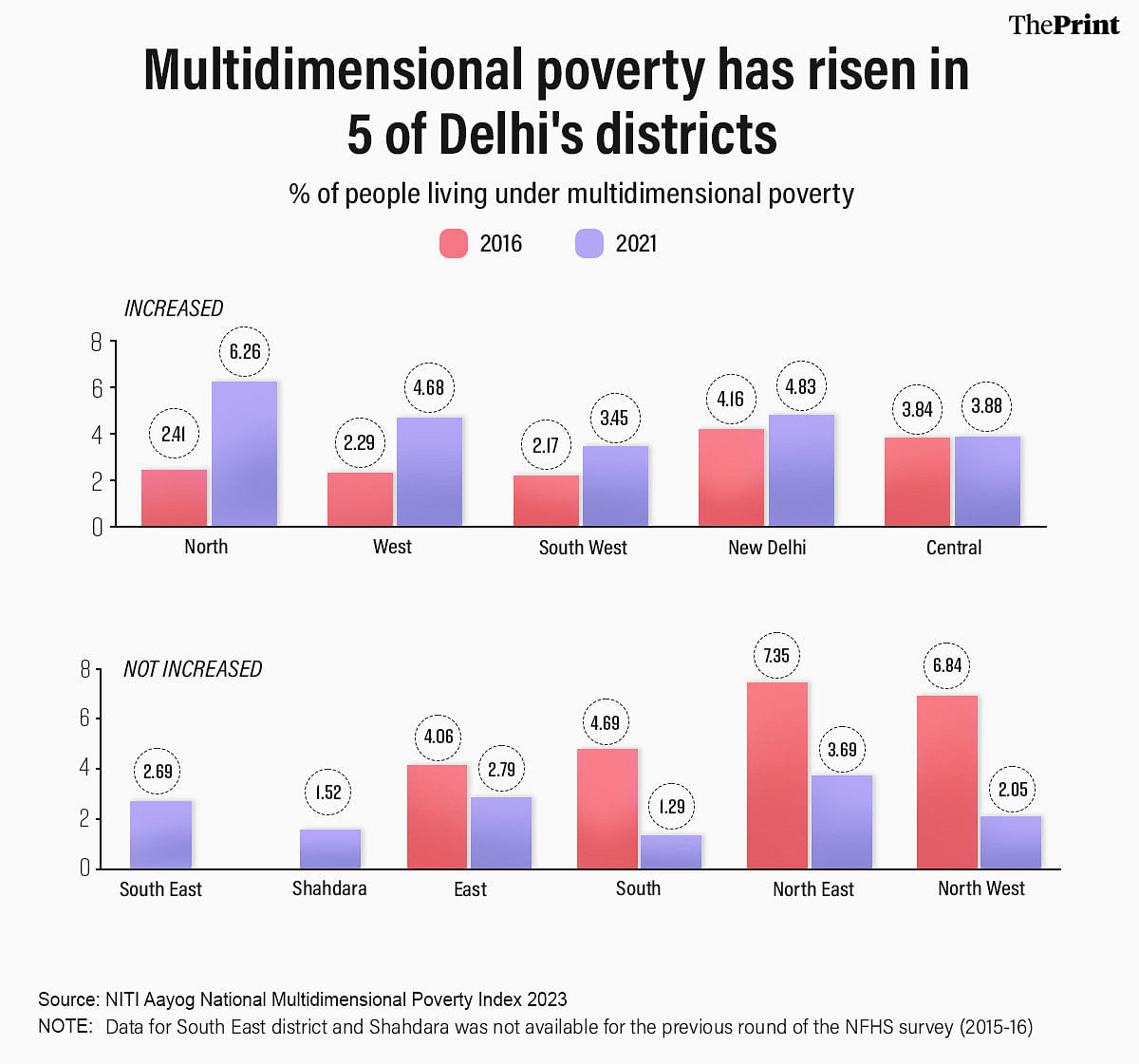

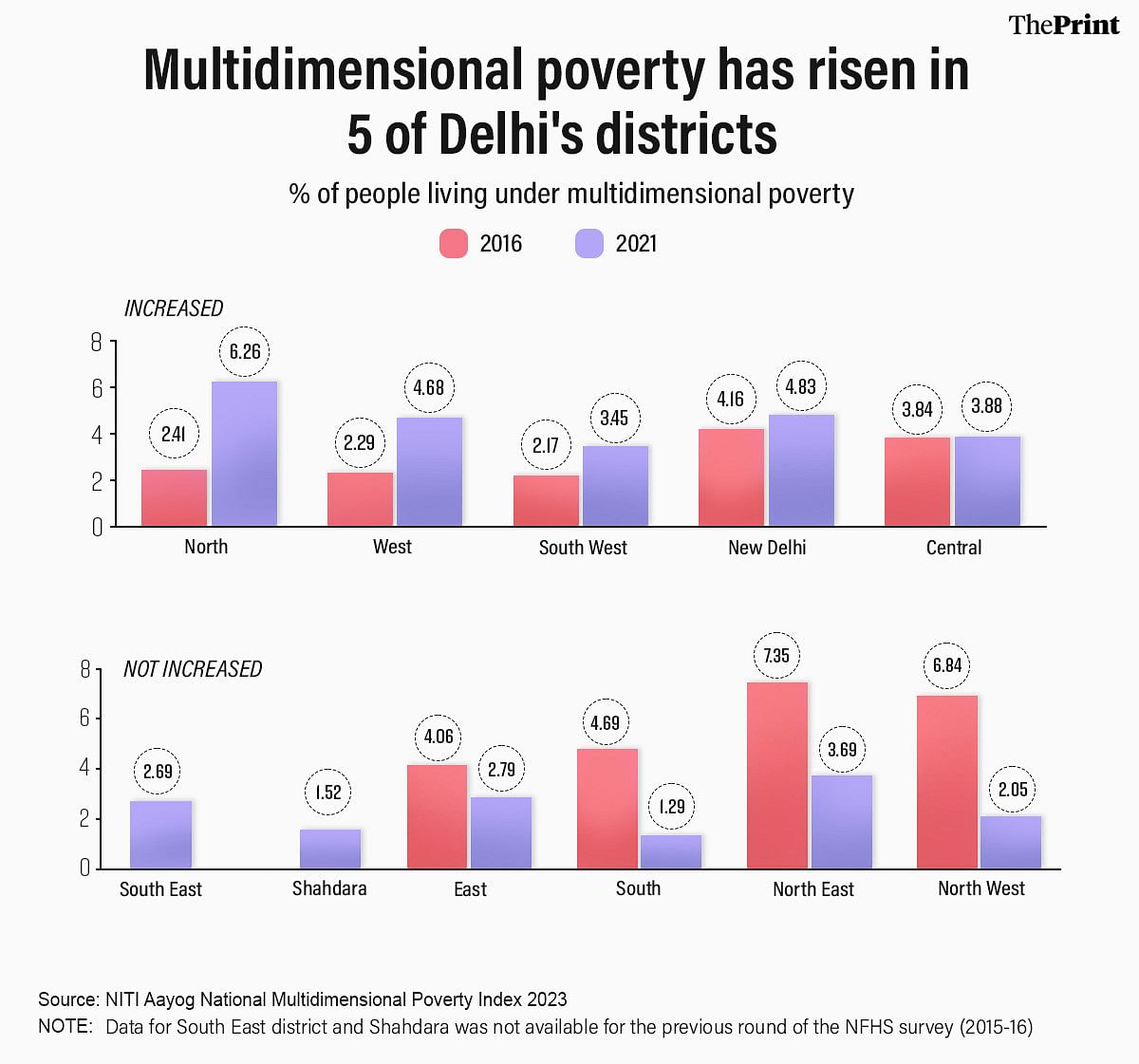

However, this overall trend masks disparities, with multidimensional poverty increasing in nearly half of the city’s 11 districts.

Among the districts of the national capital, North Delhi has witnessed the biggest increase in multidimensional poverty. In 2016, around 2.41 per cent of North Delhi’s population faced deprivation across indicators. In 2021, this escalated to 6.26 per cent.

To put it differently, there was one multidimensionally poor person for every 41 residents of North Delhi in 2016. But five years on, one in every 16 residents came under this category.

Similarly, multidimensional poverty increased in West Delhi from 2.29 per cent to 4.68 per cent, in South West Delhi from 2.16 per cent to 3.15 per cent, in New Delhi from 4.16 per cent to 4.83 per cent, and in Central Delhi from 3.84 per cent to 3.88 per cent. Together, these five districts comprise 36 per cent of Delhi’s population, according to the 2011 Census.

The MPI evaluates poverty beyond just income, considering living standards, health, and education, comprising a total of 12 sub-indicators. The report uses data from the previous two rounds of the National Family Health Survey (NFHS), conducted in 2015-16 (NFHS-4) and 2019-21 (NFHS-5).

Notably, despite the increase in multidimensional poverty in some districts, Delhi’s proportion of the population experiencing deprivation, at 3.43 per cent, is substantially lower than the national poverty headcount ratio of 14.96 per cent.

But while Delhi has seen a reduction in multidimensional poverty across most of the 12 indicators, the area of education is a significant exception.

Also Read: Gujarat may be a boom state but proportion of its people below poverty line similar to ‘laggard’ Bengal

‘School attendance deprivation’

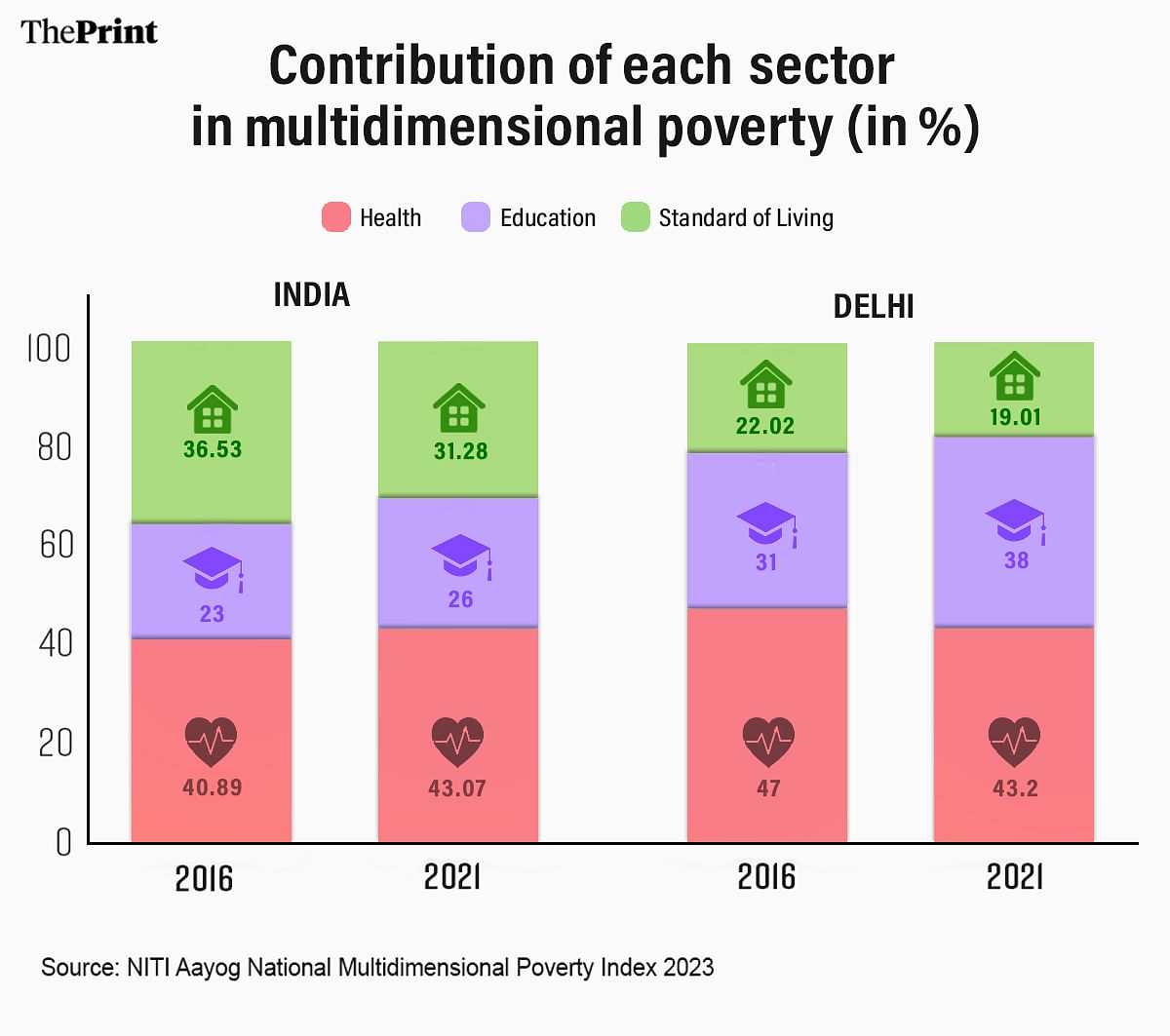

India’s reduction in multidimensional poverty has primarily been a result of improvements in standard of living indicators such as availability of water, electricity, and so on, as reported earlier by ThePrint. Health and education parameters, on the other hand, continue to pose a challenge.

In the case of Delhi, the contribution of health and standard of living to multidimensional poverty has decreased, while the contribution of educational deprivation has increased.

In 2016, health accounted for about 47 per cent of multidimensional poverty in Delhi, but this fell to 43 per cent by 2021. Similarly, the standard of living indicators, which contributed to 22.02 per cent in 2016, fell to around 19 per cent in 2021.

In contrast, the contribution of educational deprivations has increased in Delhi. In 2016, it accounted for 31 per cent of multidimensional poverty, but this rose to 38 per cent by 2021 — an 8 percentage point increase.

Looking at the data at a granular level, Delhi has witnessed an increase in the educational sub-indicator of ‘school attendance deprivation’.

According to the NITI Aayog report, a household is considered deprived in the area of school education if “any school-aged child is not attending school up to the age at which he/she would complete class 8”.

In Delhi, school attendance deprivation has risen between the two NFHS surveys.

In 2016, 2.63 per cent of families experienced deprivation on this front, which increased to 2.77 per cent by 2021.

Simply put, 263 out of 1,000 children of grade 8 age were not attending school in 2016. This number rose to 277 by 2021, signifying that an additional 14 children per 1,000 were not attending school at the age when they should have been studying in class 8.

Significantly, it’s not just Delhi where deprivation in school attendance has risen. Overall, school attendance deprivation in India has risen from 5.04 per cent to 5.27 per cent. Delhi’s increase in deprivation, therefore, is slightly below the national average. In essence, while Delhi had 14 more out-of-school children per 1,000 in 2021 than in 2016, the average for India was 21.

‘Need more data’

It is difficult to draw conclusions about the increase in Delhi’s school attendance deprivation.

For instance, since the MPI report lacks district-wise data for each indicator, it is not possible to gauge from the report if the educational deprivation correlates in any way with the increase in multidimensional poverty in some districts of the capital.

Earlier this year, Sukanya Bose of the National Institution of Public Finance and Policy (NIPFP), a think tank an ‘autonomous research institute under the Ministry of Finance, co-authored a working paper that outlined how 89 per cent of the schools run by the Delhi government faced a shortage of classrooms.

However, speaking to ThePrint, Bose said that the minute increase in the figure for school attendance deprivation in Delhi was not sufficient to make broader inferences.

“Having come to a reasonably low level, this indicator is proving to be sticky. I wouldn’t pay too much attention to the decimal point difference across rounds (of the NFHS). Notice there is a similar trend for many other relatively small advanced regions, like Puducherry and Chandigarh,” she said.

Bose, however, noted that NITI Aayog’s definition of school attendance deprivation was very narrow, and thus underestimated the extent of the problem.

She said that while the attendance indicator is “loosely defined” in NFHS, the NITI report restricts it to only “school-age children”, which means five years old and above, and whether or not they go to school until the age at which they would complete class 8.

“Pre-school is not considered at all, although the data is there in NFHS. This accounts for the high attendance rates (low deprivation). It under-estimates the problem!” she said.

“The differences (in deprivation) across Delhi’s districts and sub-regions are significant. Are we slipping further? It is difficult to say based on this attendance indicator. Some may point out that the sample size is not large enough for a district-level analysis,” she added.

Bose recommends that in order to assess the true size of the problem of educational deprivation in India, “there should be an all-India household level survey” like the National Sample Survey (NSS) rounds on education. Such a survey, she said, should include many indicators.

“This is absolutely essential in the post-Covid context, and in the absence of Census information,” she said.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

Also Read: Indian states with less than 10% multidimensional poverty doubled in 5 yrs, says NITI Aayog report